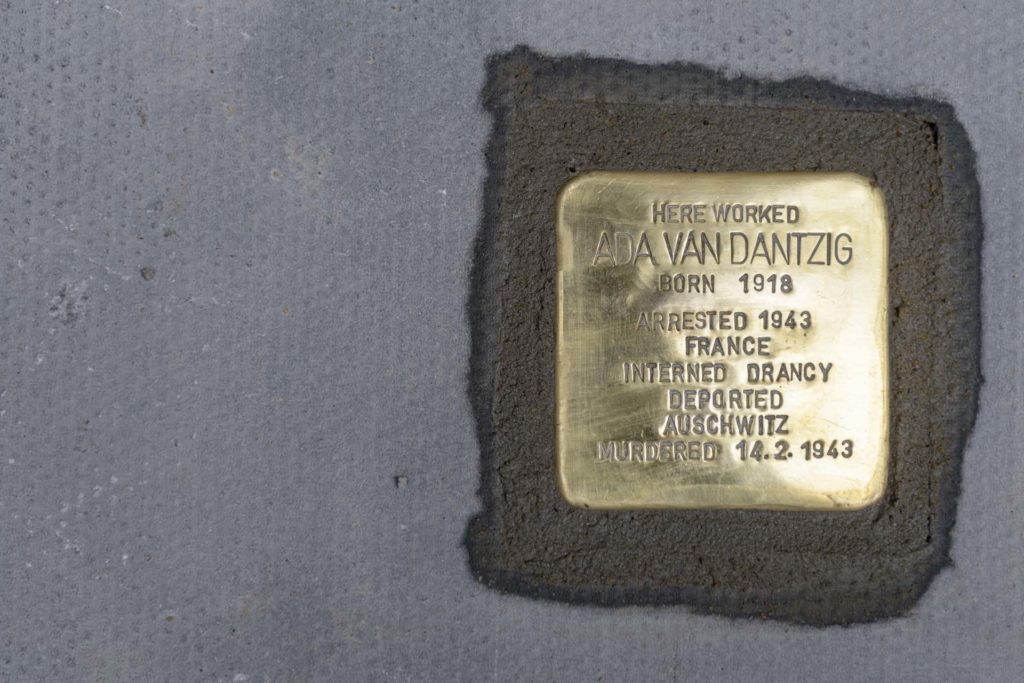

Stolperstein Ceremony - London 30 May 2022

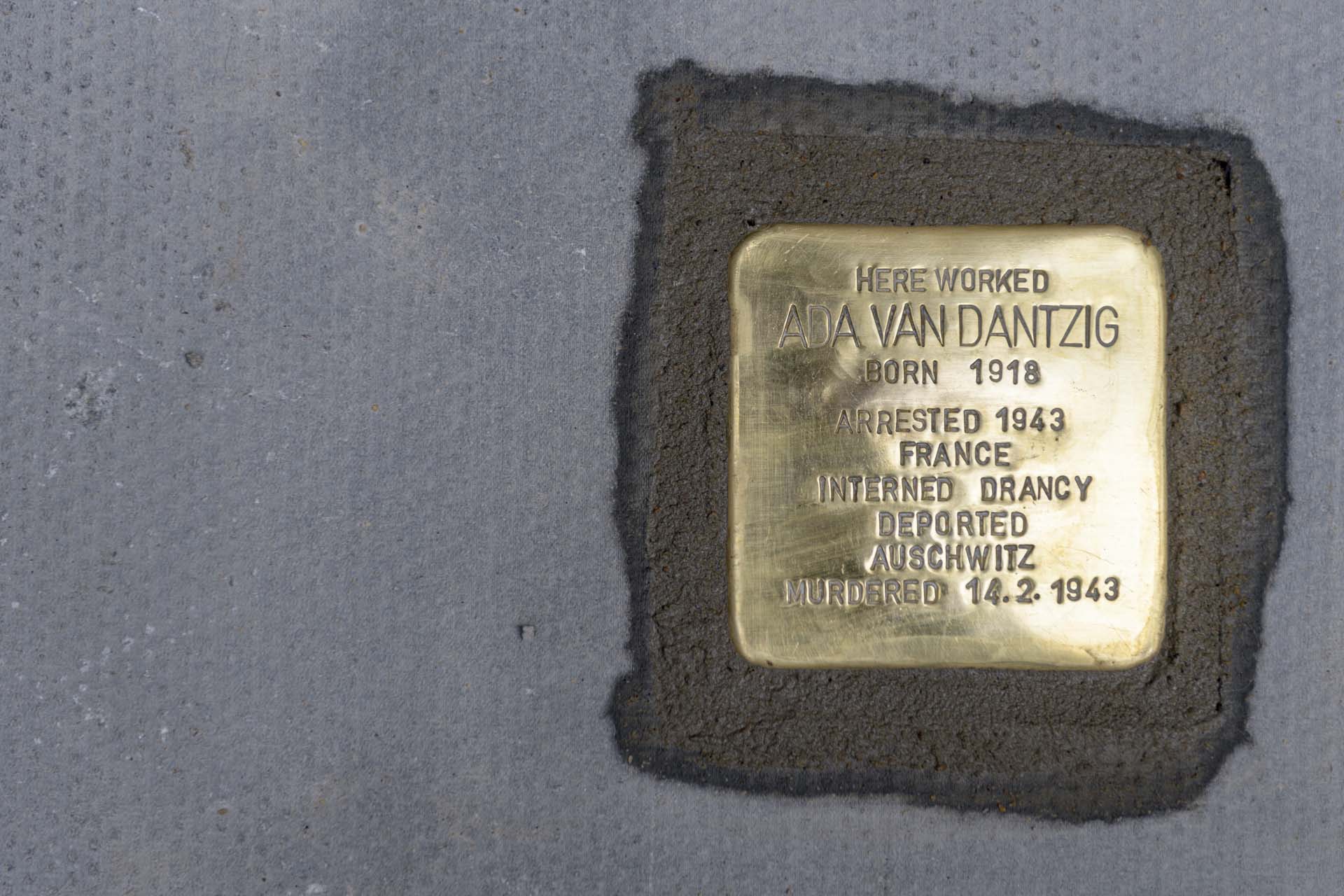

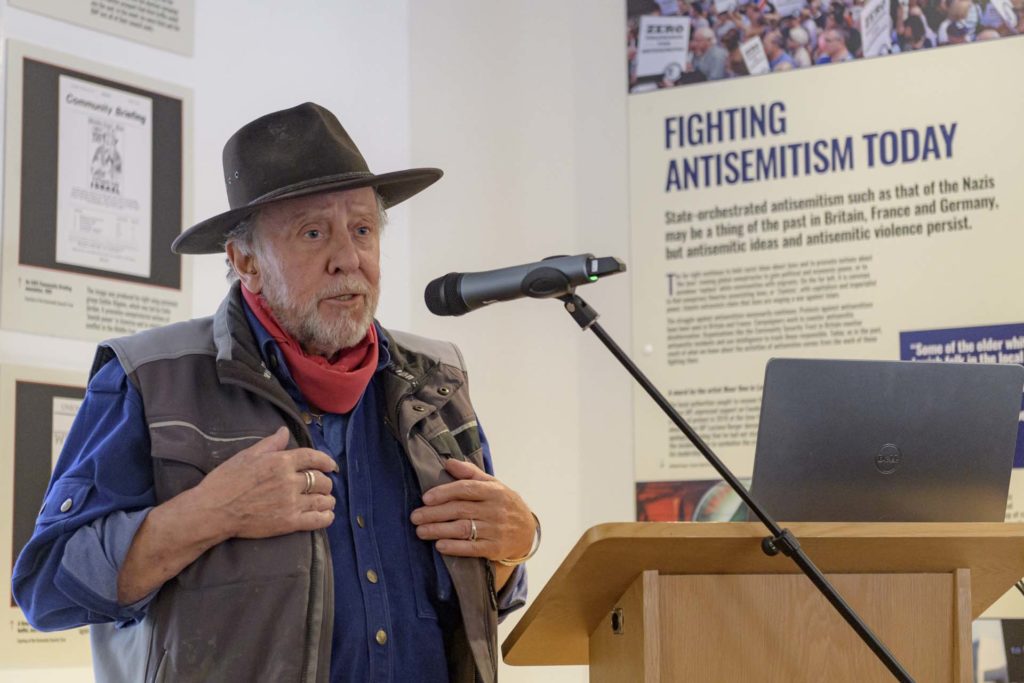

At 11.00 am the quiet man in the wide-brimmed hat detaches himself from the small crowd and moves towards the waiting bucket of mortar, trowel and mallet. On the pavement a slightly elongated cube of concrete and brass sits beside a neat hole, ground through a classic London paving slab. With the economy of considerable practice, the mortar is mixed, the hole is partially filled, the cube is dropped in and tamped down with the mallet.

Through all of this the man’s face is hidden from most people behind the hat. As the cameras click he is focussed on his work with an intensity which seems to exclude the crowd, the street noise and the city. He seems strikingly alone in what he is doing.

A final clearing of excess mortar with the trowel and a quick wipe of the brass with a sponge and the job is done. The artist stands, and it is time for various people to say a few words.

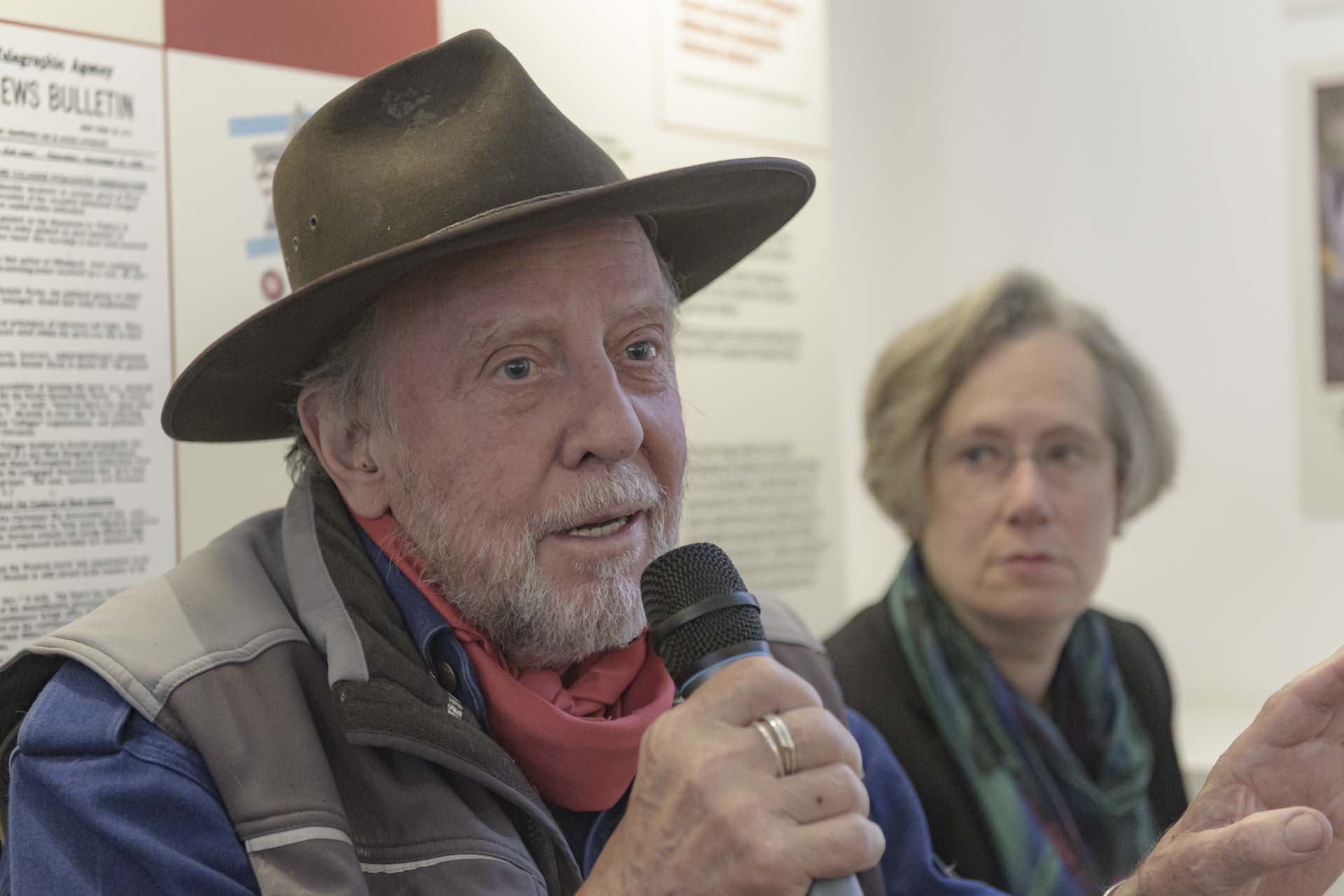

The artist is Gunter Demnig and the little brass-topped block a Stolperstein – a hand-crafted memorial to one individual who died at the hands of the Nazis. Starting with what was intended to be a one-off in 1992, there are now over 90 000 of them already across Europe, in 28 countries. An extraordinary proportion of that number have been laid by Demnig personally. This is the first such stone to be laid in the UK.

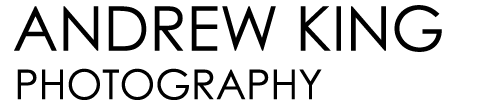

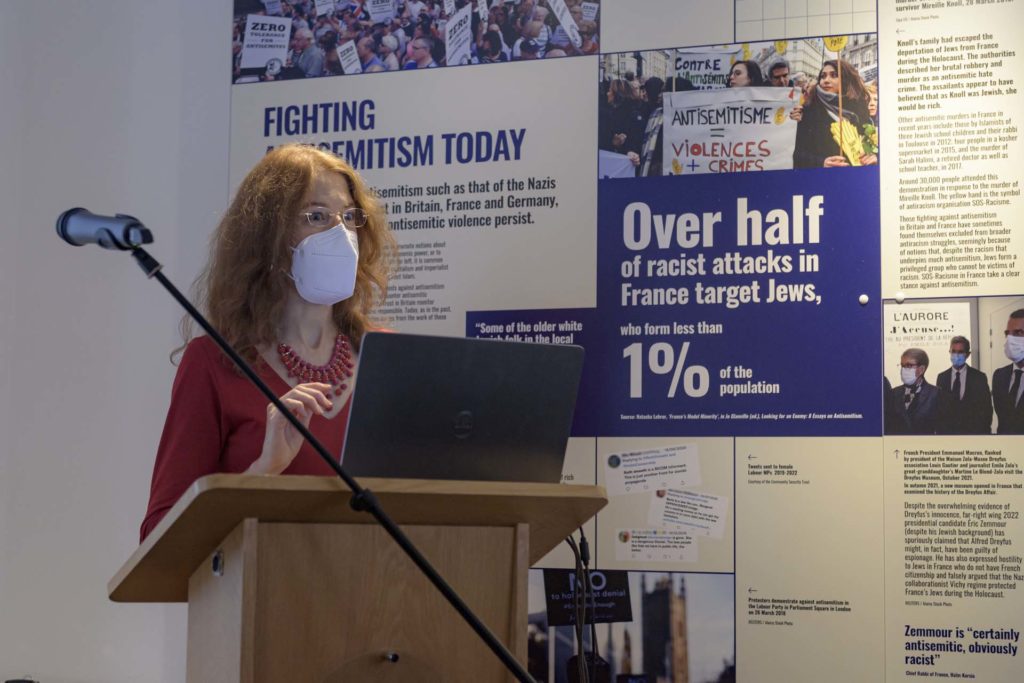

Various people speak. Clr Paul Dimoldenberg has a few words on behalf of Westminster Council. Gunter Demnig is briefer still. Prof Ruth Mandel reads the biographical statement about Ada van Dantzig, who is memorialised by the stone. The statement was prepared by the Oxford historian and paintings conservator Morwenna Blewett, but she was sadly unable to attend in person. Dr Toby Simpson speaks on behalf of the Wiener Holocaust Library, and saxophonist David Barrows plays a plantive piece by Giacinto Scelsi.

Ada van Dantzig was a young Dutch Jewish woman who came to London in the 1930s to study painting restoration and conservation. She worked with leading restorer and consultant to the National Gallery, Helmut Ruhemann, in his studio in Golden Square, Soho. Sacked from his post at the Kaiser Friedrich Museum (now the Bode Museum) in Berlin in 1933 because he was Jewish, Ruhemann had moved to London.

Together with Ruhemann and other Jewish immigrants working in the same field, Ada experienced the weight of British anti-refugee, anti-immigrant and anti-semitic prejudice. Helmut Ruhemann is to this day regarded as one of the most significant figures in the history of painting restoration; at the time his work and the work of the apprentices under him was highly praised. And yet they were paid on a significantly lower scale than British restorers, and experienced the myriad of social ostracisms that, together, remind the incomer on a daily basis that they are not “one of us.” This may have been one reason why Ruhemann set up his own studio/workshop, away from the Gallery. Number 2 Golden Square became a haven where refugee status and Jewishness were no bar to acceptance. “Physical and legally enshrined persecution in Berlin was swapped for open prejudice, social ostracism and sistemic discrimination in London.”

As war loomed, Ada van Dantzig became concerned for her family in the Netherlands. Against the advice and pleas of friends and colleagues, she returned to Rotterdam in 1939. The family stayed in the city, under occupation, until early 1943, when they decided to try to reach neutral Switzerland.

Ada and her parents, her sister and one of her brothers were arrested in France and interned in the Drancy transit camp. From there, the family were taken to Auschwitz where they were murdered. Ada died on 14 February 1943.

After the laying of the Stolperstein and a break for lunch we reconvene at the Wiener Holocaust Library in Russell Square. An introduction by Dr Toby Simpson, and again we listen to David Barrows’ sax. Then we hear again from Gunter and Ruth, together with presentations from Drs Gaby Glassman, Andy Pierce and Gilly Carr. Dr Mandel repeats the earlier biographical statement on Ada van Dantzig prepared by Morwenna Blewett, and others speak on themes of memorialisation and inter-generational memory, ending with a lively and lengthy talk on the differing approaches to memorialisation of the victims of the German occupation of the Channel Islands. The whole session can be viewed on the Wiener Holocaust Library’s YouTube channel.

What I am left with from the day is the driving force that exists in Gunter Demnig. I sense a private man under that hat, a man whose original idea has in a sense gained a life of its own, bigger than him, and yet an idea to which he is still absolutely committed with no let-up whatsoever.

Gunter is asked how he now feels about the Stolpersteine, after 90 000 of them have been laid. “If you are asking me if it is now a routine, no, it is not. Every one of them is individual, it is for a person.”

His eyes shine.

Each Stolperstein is handmade – visibly so. They are individual and they commemorate individuals. The hammering in of the letters of the name and the brief biographical details (Here lived… murdered at… with the dates); the individual placing of the stones at the last known “address of choice”; the artist mixing the mortar, the tamping down – all of it is personal, deliberate, connecting.

The Stolperstein concept has not been without its critics. The location of the stones in pavements has been criticised, from being simply disrespectful to the more sharply anguished claim that “They are still trampling on us”. But over against that, the simplicity of the idea and what has become its sheer scale argue for themselves. Yes, they may be walked over, all unconscious, but once seen they draw the eye down. On pavements outside thousands of buildings, people now stop briefly to bow their heads or drop to their knees to read a name.

The Stolpersteine project has become the world’s largest decentralised memorial and art installation. It is both massive and yet deliberately and precisely individual. By locating a name at an address of residence or work it brings the Holocaust right home: “This person lived and work here until they were taken and killed.” Gunter Demnig often cites the Talmud as saying that a person is only forgotten when their name is forgotten. I haven’t been able to find the reference in the Talmud, though I have found similar words in Terry Pratchett! Whatever the origin, it is a remarkable quote, and totally apposite: Stolpersteine memorialise precisely at the level of names.

And for many, for most, this is the only gravestone, the only individual memorial there will be. Perhaps the deepest part of the day for me was a conversation I saw and overheard:

An older woman holds up two A4 sheets – photocopies of pictures of two Berlin Stolpersteine.

I hear her words, “These are my parents.”

Image of Ada van Dantzig found on the web – I do not know the origin – please inform me if any infringement has occurred. All other images by Andrew King copyright © Andrew King Photography. If you would like to print or use an image, please just contact me.

Image of Berlin Stolpersteine Nikon D700 with Nikkor 50mm 1.4G.

Images from the London Stolperstein ceremony and Wiener Holocaust Library lectures Nikon D800 with Samyang 12mm f 2.8 fisheye and D5 with Nikkor 24-70 f2.8

For more photography and articles focussed on WWII and the Holocaust, please see my previous blogs:

and