The Kindertransport Memorials - New Connections Made

Since I last wrote on the subject of Frank Meisler’s Kindertransport Statues, much has happened. Following the publication of that blog, I was contacted by Dr Amy Williams, a historian working in the whole area of the memorials of the Kindertransport. She set up a zoom call with me and Bill Niven, who was Amy’s supervisor through her PhD and is still a mentor and collaborator in post-doctoral work. This conversation was both interesting – it’s great to talk with people who really know about anything – and encouraging as it has opened up possible avenues of collaboration. Very few people have seen all of Frank’s memorial sculptures; even fewer have seen them in one purposeful journey. Our own journey and our thoughts and feelings about it are in themselves material for Amy’s research; our photos may be of value to her in illustration of her work. And from my point of view, as we look to write up and possibly publish the images from our journey, contact with a specialist historian will be an enormous help. Plans are afoot!

This week I had the opportunity to meet Amy and join her on a whistle stop tour of Liverpool and Paddington stations, and then a trip to the Imperial War Museum. In some ways the day brought back memories of our Kindertransport journey in 2015, and seeing some of the same things but with someone who knows so much was a great experience. This blog is a quick write up of the day.

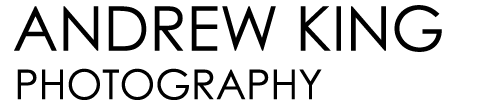

The Kindertransport Memorials - Liverpool Street

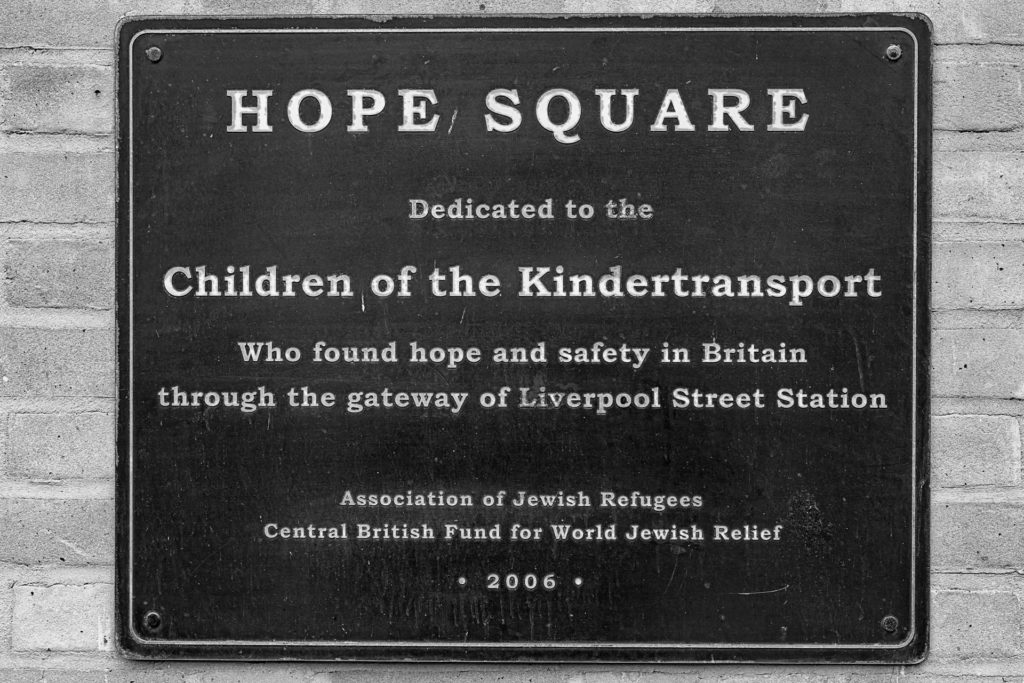

Liverpool Street Station has two Kindertransport memorial sculpture groups. The Frank Meisler ones are at street level in Hope Square at the main (Eastern) entrance of the station. It’s a good location, except for the fact that they are very much subject to the presence of pigeons, scourge of London’s outdoor statue and sculpture community.

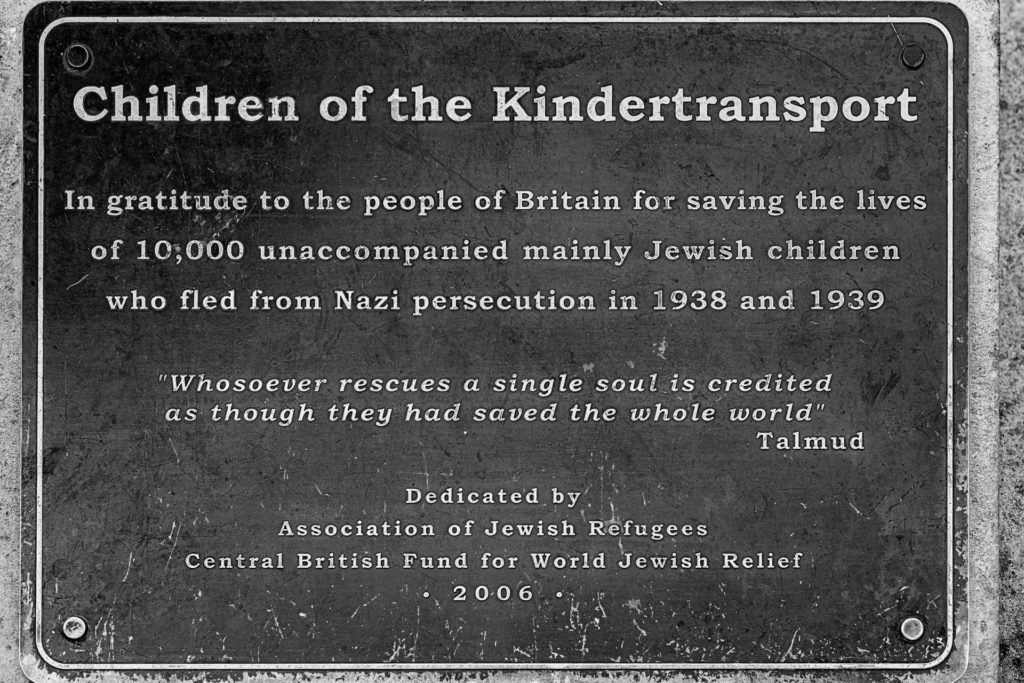

Downstairs, inside the station, just alongside the Underground entrance are two more children, by the artist Flor Kent. Like the Meisler sculptures, these have corresponding pieces on the continent – in Prague and Vienna – but are perhaps associated more particularly with the work of Sir Nicholas Winton. This was the first time I had set about photographing the Flor Kent pieces in a serious way.

When we completed our Kindertransport journey in 2015, our train was severely delayed on the way in from Harwich and we only arrived well after midnight. Sheer tiredness cut short our photographic work at the time, although the shots we did get (uploaded on the last blog) are all the more atmospheric for being at night. We have taken some pictures every time we have passed the spot since, but this was my most concentrated piece of work on them yet.

One detail that I learned from Amy: the lad with a pen in his pocket, who is visible in the other groups too, starting in Gdansk, is Frank Meisler himself! The pen suits the aspiring architect – as does the fact that, of all the group, he is the one looking around at the buildings of the City with the most positive expression on his face. In my brief correspondence with Frank before his death, he told me that the mood he wanted to evoke with the London group was exactly one of “nervousness, awe, lostness and yet of excitement and new beginning.” I love these works. They repay close inspection.

As you can see, the pigeons are a real issue. We do not remember the children being this messy before, and it raises the question of whether and when they are cleaned. I would very much like to know when there may be a chance to photograph them without guano! If anyone reading this can offer any help or advice (even advice on how to clean droppings off bronze statues!) I would be glad to hear from you.

The two children in the Flor Kent memorial inside the station also repay attention and thought. They are somewhat enigmatic. There is a battered suitcase, but no numbered labels. The boy has a yarmulke – a more obvious sign of Jewishness than the Meisler children – but in other respects both the children seem timeless and stateless and not so tied to the 1930s in their clothing. The boy’s shoes look more like modern trainers, and the girl wears a badge which I believe is associated with more recent commemorations of the Kindertransport, not the rescue itself.

I like this universalising element. The broad title of the work – “For the children” in German and Czech – seems to make these Jewish Kinder emblematic of every orphaned and dispossessed and fleeing child in every conflict since 1939.

This is still very much a Kindertransport memorial, though. While I was looking and taking my pictures, I was approached by a rabbi – he looked (and is) just a little older than me. “The little girl looks exactly as my mother did when she arrived in 1939.” Rabbi Herschel Gluck OBE is an Orthodox Jewish rabbi based in Stamford Hill, and the founder and chair of the Muslim-Jewish forum. It was a privilege to meet him.

The Paddington Statue - Paddington Station

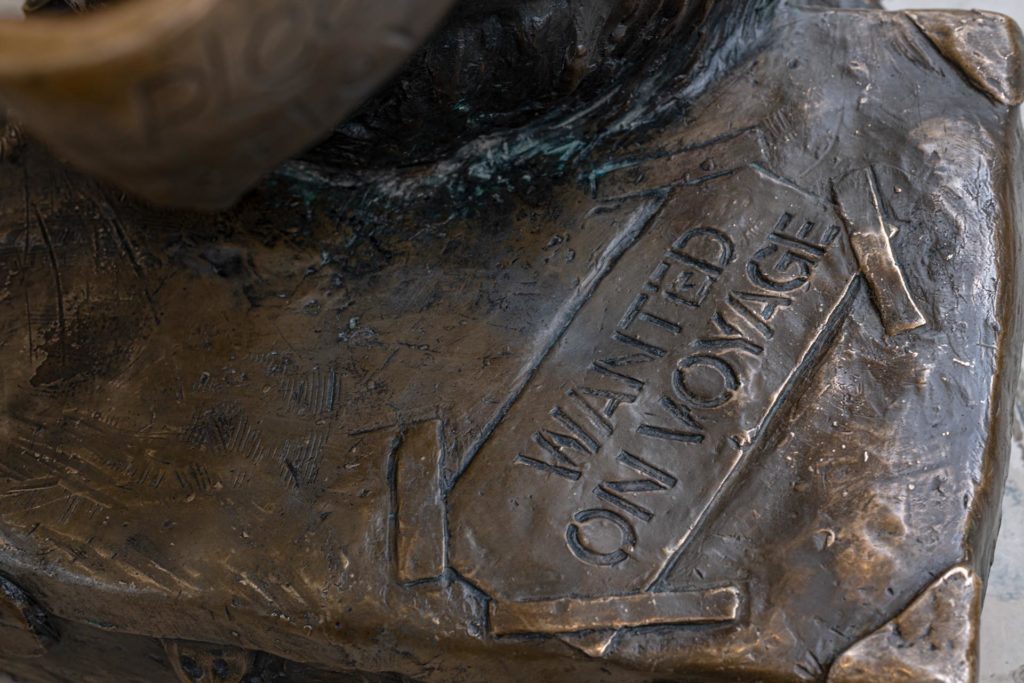

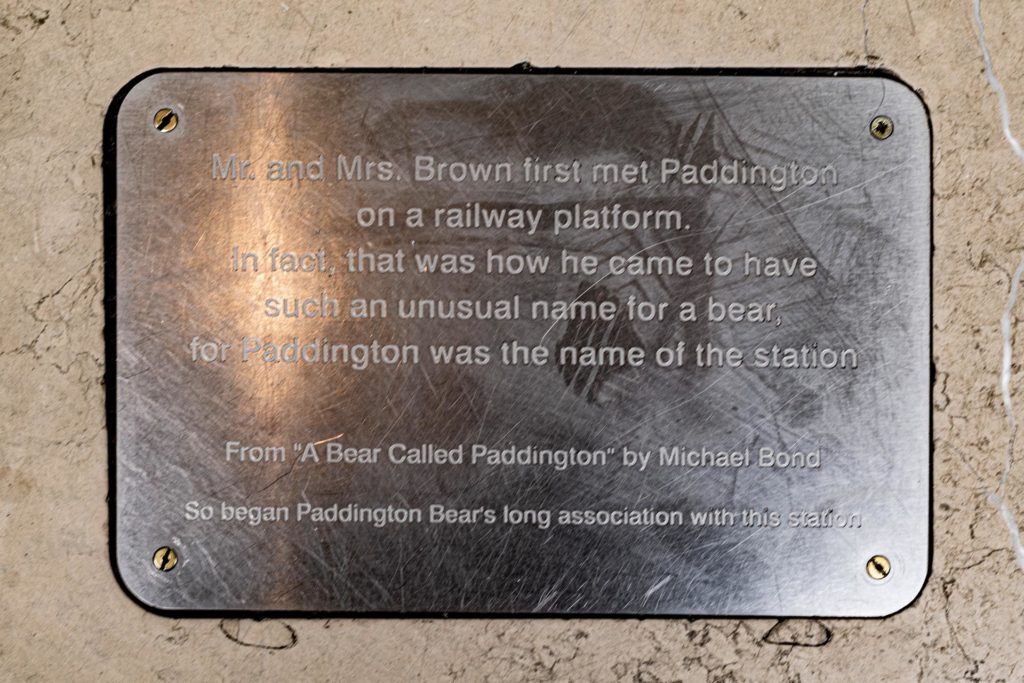

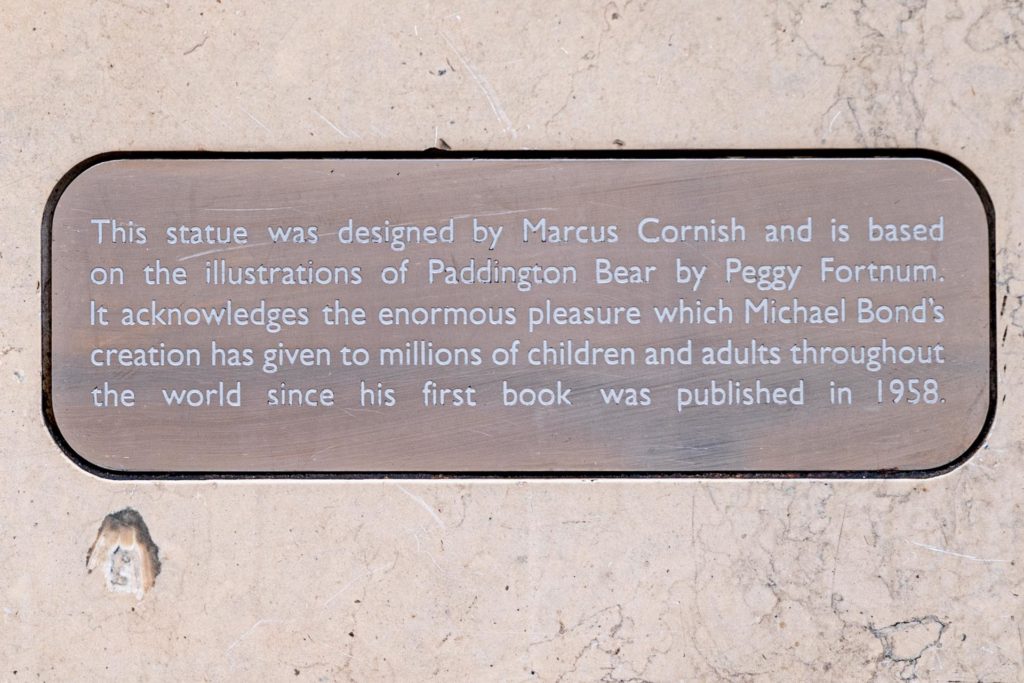

What has Paddington got to do with the Kindertransport, you may ask? At one level, nothing at all. The loveable and bungling bear is from Peru and arrived at Paddington (Brunel’s broad gauge line to Lima is a little-known quirk of the British railways system!). The books and films are loved all over the world by people who would never make a link with World War II and the Holocaust.

But have a think for a moment. Orphaned by an earthquake, brought up by his aunt until she was too old to look after him, he arrived at a London station with a label tied to him, “Please look after this bear” – committed into the care of strangers. As if this is not enough to make the connections, Paddington’s best friend is Mr Gruber – a Hungarian immigrant whose first name is Samuel.

With those thoughts in mind, it is no surprise to find that Michael Bond, the author of the Paddington books cited the London evacuations and the Kindertransport as being the models for his orphaned, refugee bear. Paddington really is a Kindertransport memorial!

The Imperial War Museum

The Imperial War Museum – now generally called the IWM – in London houses Britain’s largest exhibition relating to the Holocaust. It is not permitted to take photographs in the Holocaust galleries, so I have none from my visit – mine here are from Auschwitz.

Many thoughts from the day. Here are a few:

- The uncomfortable wisdom of visiting Auschwitz at the beginning of our Kindertransport journey was brought home to me – though this day was in reverse order, going from Hope Square to the Holocaust itself. The children are called Survivors – survivors of what? They were rescued – rescued from what? Only by staring into the abyss do you get a sense of the gravity and urgency of the attempts to save human beings. The Kindertransport is only seen to have any point and purpose, beauty or value as you look at the alternative. The same goes for other projects that speak of “salvation.”

2. The poverty and littleness of the rescue effort is brought home yet again. Some 10 000 children were saved from death by the Kindertransport. A further 80 000 or so mainly Jewish refugees found shelter in the UK from the killings. This sounds like a lot of people, but when you consider that the camps were “processing” (how I hate that word being used now by the UK government!) some 15 000 people per day between August and October 1942 you realise that we didn’t even save a week’s worth.

3. The fact that the story of the Kindertransport is as much as anything the story of a few compassionately stubborn individuals struggling to overcome the inertia, lack of compassion and downright obstructionism of the government and establishment, including some of our best-known newspapers. This has struck me before, but in the light of the disgraceful behaviour of our present corrupt government it just seems so relevant.

One picture in the IWM struck me especially – I found and downloaded it this morning. Oskar Goldberg was one of a group of Czech Jews fleeing the Nazis in March 1939. They chartered a plane and landed at Croydon airport. They were sent back to their plane, and Oskar decided to resist. This is is how he was carried back to the aircraft. Bear in mind – this is months after the Nazi take-over of a large swathe of Czechoslovakia, months after the appalling Kristallnacht violence against the Jews and two weeks after the remainder of Czechoslovakia has effectively come under Nazi rule as a protectorate. There could have been no doubt that these people were in desperate danger – but they didn’t have the financial guarantees and sponsors to stay.

When even Theresa “Hostile Environment” May can thunder at the illegality and dangers of Priti Patel’s Rwanda plans, I cannot see how the present government can look us, the people, in the eye and say that it would have done any differently.

In the event, Goldberg and his party were allowed to stay. His quick decision to resist deportation probably saved his and his friends’ lives – the Danish pilot refused to take off with them, and that bought time for Jews in London to step forward and give the financial guarantees. To read more on this event and its impact, see here.

4. The sheer awfulness of the Holocaust. The new galleries at the IWM are very powerful. They make use of some film footage I haven’t seen before – of high quality and shown on large screens. To walk into a room and see moving images of naked human bodies being manhandled onto the back of a lorry like so many animal carcasses left me feeling as if I were staring into hell itself.

I have seen and been made to think of these things from time to time since I was a child. I am now in training to be an old man. Time and exposure cannot diminish the awfulness of what was done in that period. To deny it happened is wicked; I would say that denial is to connive in the evil.

What was done was done in greatest measure to the Jewish people. Around 6 million Jews – two thirds of Europe’s entire Jewish population – died at the hands of the Nazis. The recent increase in the recognition of other murdered groups – perhaps half a million Roma, or between 25 and 50% of the European total, perhaps 100 000 gay men – is welcome, but must not obscure the overwhelming weight in numbers of the Jewish suffering.

Amy and I were in the IWM on 28 April – Yom HaShoah, the Holocaust Memorial Day for Jews in Israel and around the world. It was a weighty day to be there. Everyone should think about these things; everyone should get themselves a world view that includes the reality of evil and of justice.

5. The importance of memorials and of historiography. We are approaching the 85th anniversary of the Kindertransport. It will be the last major anniversary at which a substantial number of the rescued children are still alive. Many of them have spent their lives telling the story, giving their testimony of what happened to them and to their families. Their voices will shortly be silenced.

Preserving memories, creating memorials, writing the history – these things are important. The last few months have shown us all over again the sheer capacity for evil that is in the human race. The potential for a descent into Gehenna, and the importance of rescue and welcome to refugees in the past, should be held before us as we face yet another European war.

It was a great privilege to visit the memorials and the IWM with a historian – a specialist in the field. Amy is, in effect, a historian of Holocaust history. There is a historiography of historiography here – How has the narrative changed, been spun? How does THIS incarnation of the IWM’s Holocaust Galleries differ from the last? Why? Those questions are not academic irrelevancies – to interrogate the historians themselves is in itself a work of history, and the answers may actually be as pressingly and practically relevant as the reminder of the events themselves. I am very grateful to Amy for being my guide through some of these things – so glad that we have this link!

The Kindertransport Statues of Frank Meisler - Work to be done

The last few months have rekindled the desire to create a book about Frank Meisler’s Kindertransport Statues. Meeting Amy and Bill has brought the promise of some serious historical care in the written parts of the work. I hope that we can also do justice to the artistic approach and methods that Frank used – sadly no longer first hand from this Kindertransport survivor as he died in 2018, but through his daughter Marit who now runs the Meisler workshop in Tel Aviv.

And as well as the book… why not a film…? Watch this space!

If you have any comments or questions about anything in this blog, please get in touch – you can use my Contact Form from the site here. Your interest and support is really valuable to me!

New images of Liverpool Street and Paddington taken on a Nikon D5, with Nikkor 70-200 2.8, Nikkor 50mm 1.4 and Samyang 10mm f3.5. They are copyright material, not for copying, printing, publication or reuse without permission.

Photos by Andrew and Sarah King, copyright © Andrew King Photography except for images explicitly identified as being by other photographers – used under Creative Commons licence or on a fair use basis. Please contact me if there is any problem.