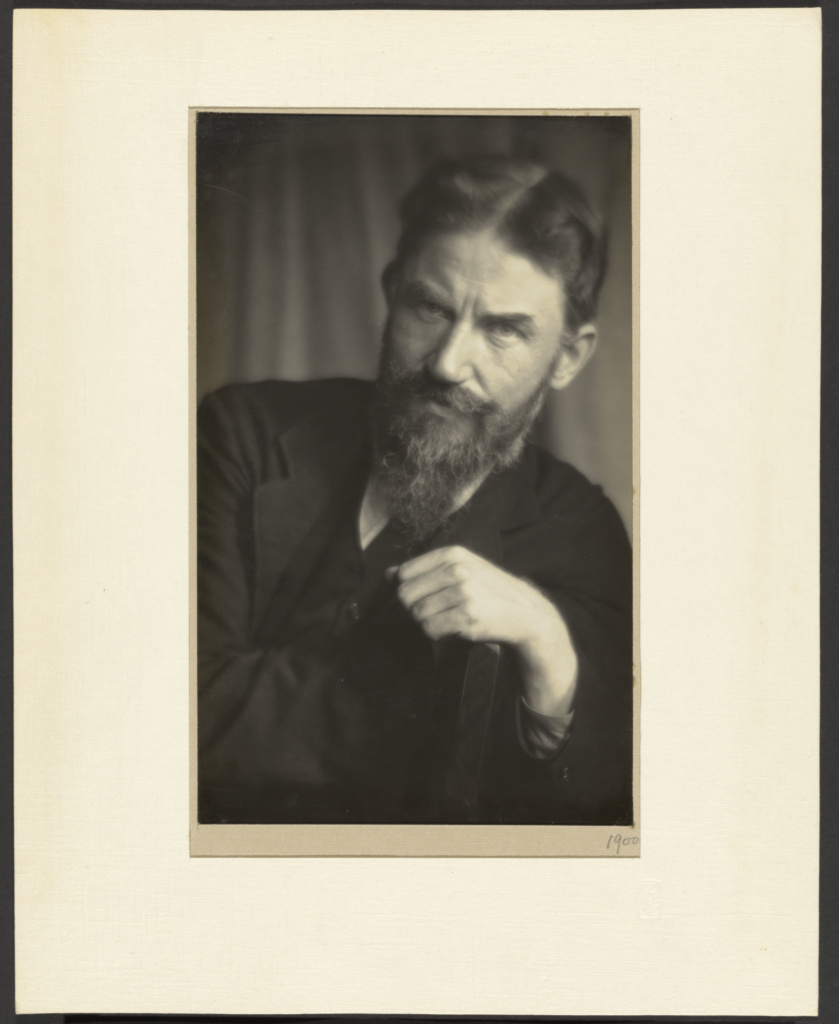

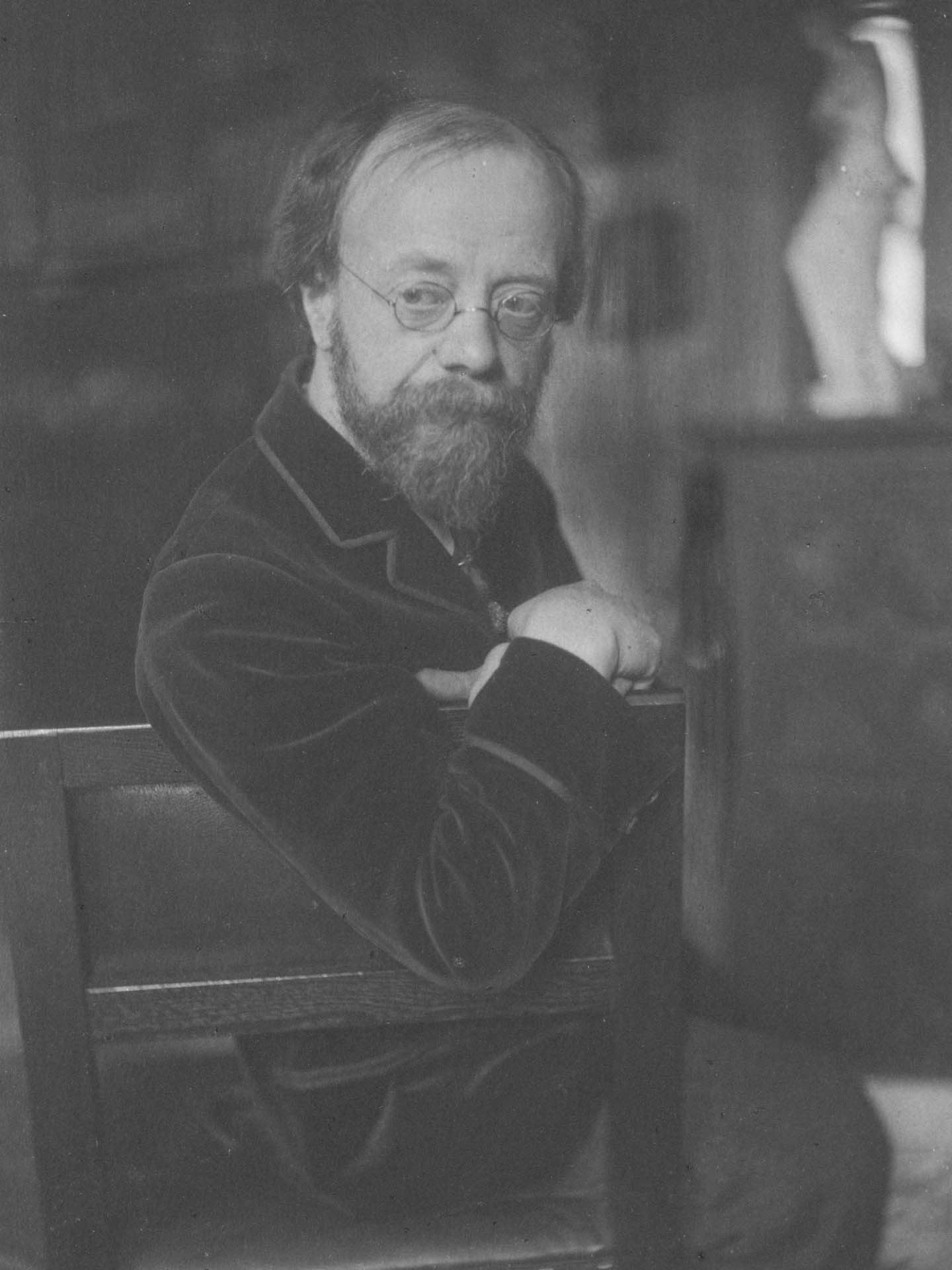

Frederick Evans 1853 – 1943

One of my favourite books, and one I thoroughly recommend to anyone interested in photography as both science and art, is Beaumont Newhall’s The History of Photography. It’s that Science AND Art thing that makes it stand out, I think – it is really comprehensive and balanced between those two aspects of picture taking. The book includes many arresting and important photos; one that has always struck me is by Frederick Evans – an image of steps in Wells Cathedral. I will come back to it.

Frederick Evans was a British photographer active at the end of the 19th and into the early 20th century. Originally a bookseller, he only worked as a dedicated photographer for a relatively short period, from 1898 to 1915. This was in part due to his own perfectionism: he latched onto the new technology of platinum-based printing as giving him the very best dynamic range he could find for his work. Unfortunately, his exclusive commitment to that medium came at a time when platinum rocketed up in price (perhaps in part because of the technology? I don’t know!) and he found himself unable to sustain his business as costs rose.

His perfectionism may have been his undoing, but it was also, of course, his strength. He is recognised as one of the greatest architectural photographers who has ever lived. George Bernard Shaw said of him, “Mr. Evans has set a standard in photography that most of us find entirely impossible to live up to. He is a gentleman who has dedicated himself to an art which is disparaged by those who believe that when a lens is in a box it is mechanical, but not when it is in a man’s head.”

Evans was highly competent in many fields as a photographer: he photographed people (there is a sequence of lovely portraits of his wife, as well as well-known images of George Bernard Shaw and Aubrey Beardsley), he photographed landscapes, he was an expert on micro-photography amongst other skill sets. But he is best known for his superlative interior architectural images, and especially for his photographs of the cathedrals of Great Britain and Western Europe.

George Bernard Shaw – 1900

A river in France

Mrs Frederick Evans around 1900

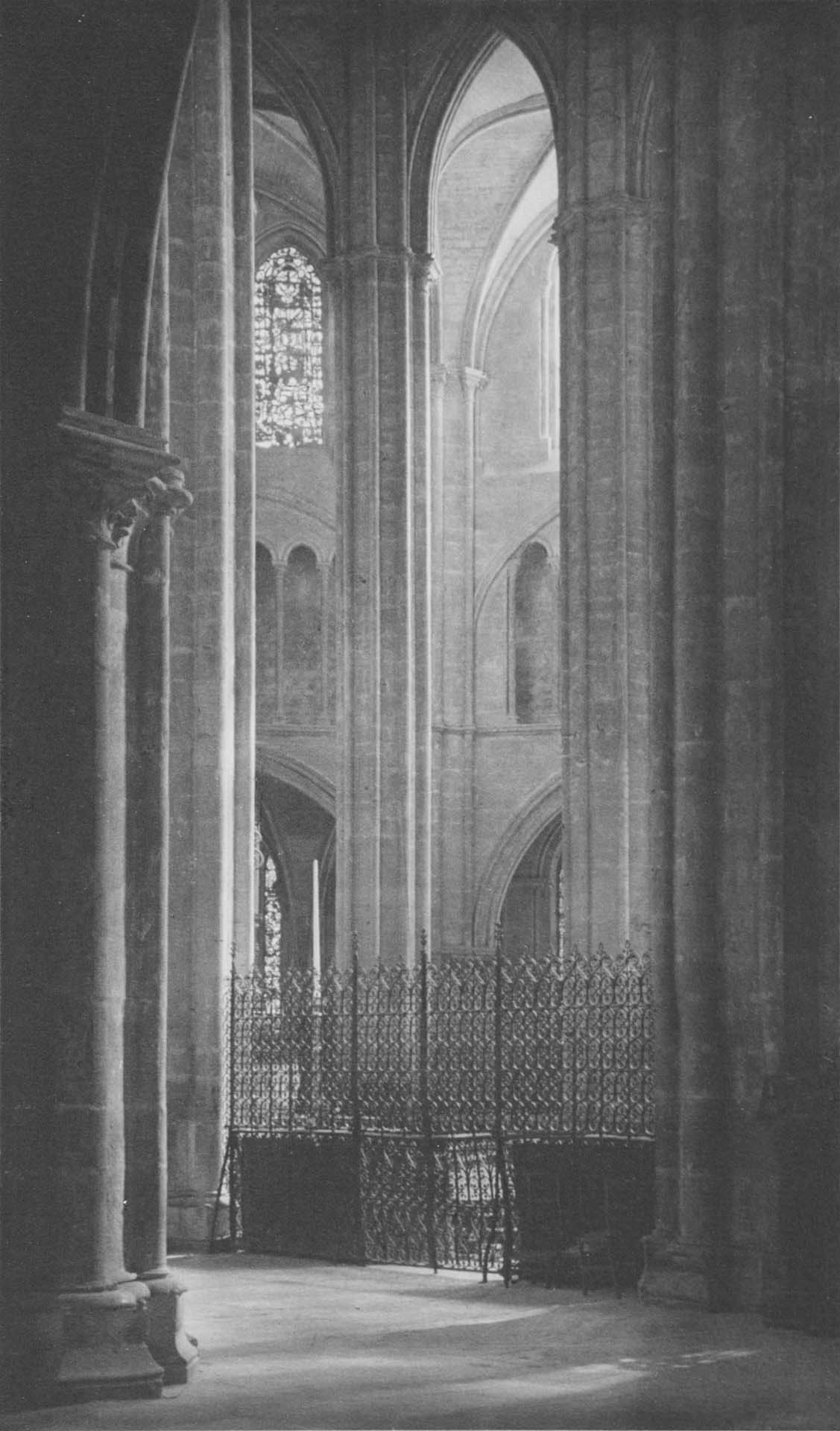

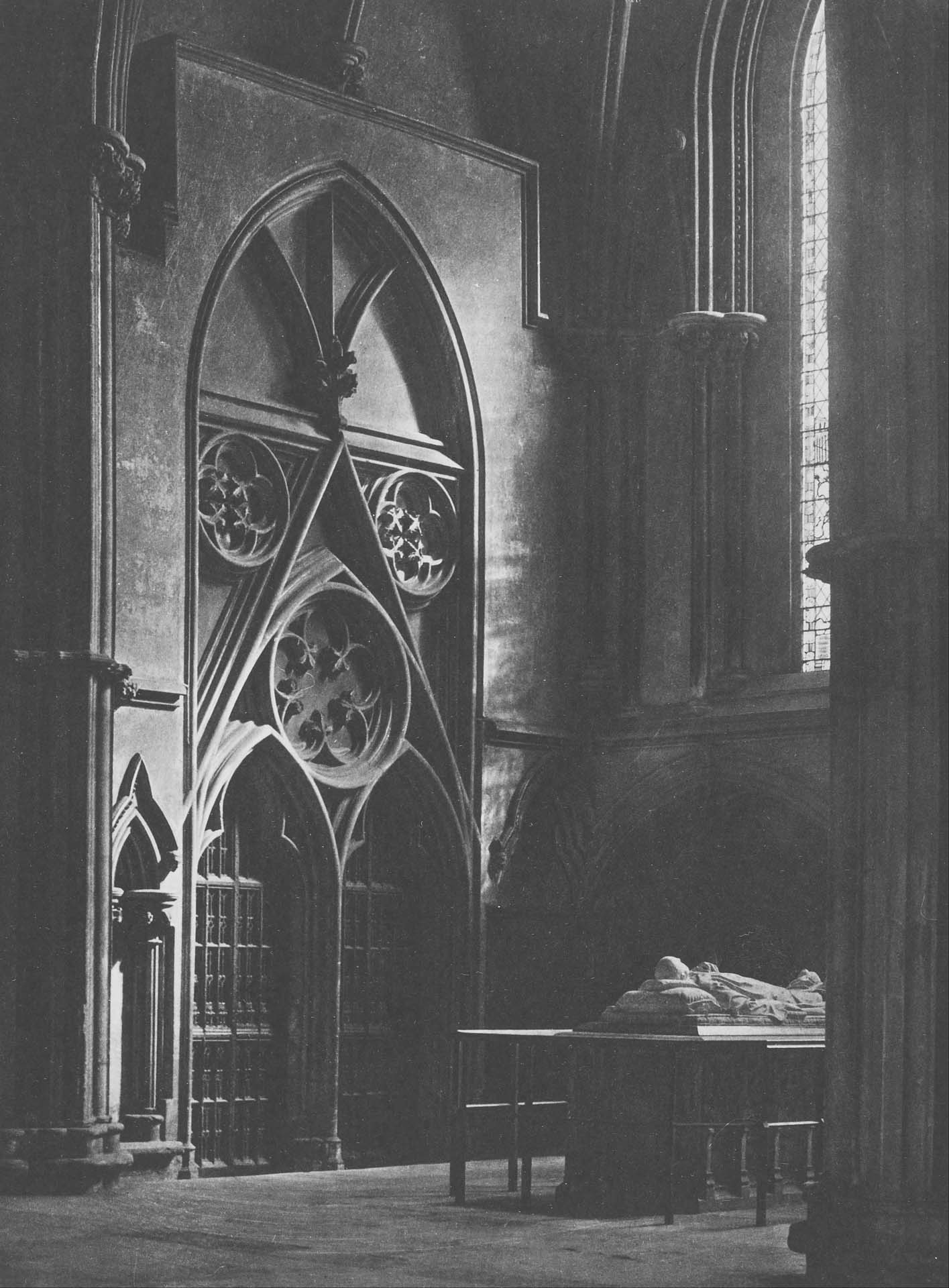

It is Evans’ architectural work that grabs me. And not simply for its technical excellence, but for its emotional impact. His photographs communicate a sense of space, of light and of peace that transcends mere printing technique.

His technique was extraordinary, of course. He was the purists’ purist. He believed that the negative must not be interfered with in the printing process; his task was to so choose time and length of exposure, plate and lens and camera position, that what his camera saw was worthy of printing with no further alteration.

Even at a time when a photographer was a kind of alchemist, with all the mistique of plates and chemicals, Evans must have had a special magic. One article on his work gives us this pen portrait of the man: One day back in the 1890s a visitor was announced to the Dean of a well-known English cathedral. The card showed the name and address of a bookseller in the City of London. Admitting the caller, the Dean saw a small, fragile-looking gentleman wearing an outlandish silk collar, a blue tie and a crushed soft hat. ‘I have come to ask for permission to photograph your cathedral.’ The Dean, after a momentary hesitation, agreed that this could be done. ‘I shall start on such and such a day,’ calmly continued the visitor, ‘and, by the way, the rows of chairs in the nave would disturb the composition of the picture. Will you please have them removed before my arrival?’

Height and Light in Bourges Cathedral

In Sure and Certain Hope

That comment that he would arrive on “such and such a day” is very telling. The process of photographing a cathedral was weeks long. Evans would take days to simply observe the light at different times. The exposures themselves would often take several hours – still a good technique to lose any people who happen to wander through the shot, although I suspect that more often than not he managed to work with a fairly empty building. The same dedication was brought to the printing process; the platinotype method gave Evans the best way (he felt) to reduce the extremely wide dynamic range (difference betweeen light and shade) of his subjects and get it onto paper in a way which still did justice to the shades of grey.

The result of this care and obsession with technical excellence is a set of images which are perfect. But not merely technically. The mastery of technique has a goal in view: the communication of the sense of awe, of enlightenment, of peace, of hope, which he felt on seeing the building he was to photograph.

At the end of the 19th century there were many who disparaged the “new art” of photography as not being art at all. It is striking to me that Evans’ goal in all that technical finickiness was absolutely artistic. His aim was to convey emotion. As he put it, “If success be to convey to another the vital aspect and feeling of the original subject, so to translate one’s own enjoyment of a scene into a visible record as to affect the critic with the very quality of one’s own original emotion, then surely it matters not in what form or method of art it be achieved, it will be as vitally valuable: and if it be possible by way of the condemned “box with a glass in it,” so much the more credit to the worker who uses that despised tool to so good an end.”

That is what I see and feel in Evans’ work. Emotion. Many of his photographs are of “sacred spaces”, but even his work in “secular” locations carries the same sense of the heart – of peace, of joy, even of the numinous.

Ancient crypt – Cellars in Provins 1910

I have to admit to a certain joy when I read those words, “so to translate one’s own enjoyment of a scene into a visible record as to affect the critic with the very quality of one’s own original emotion”. Living and working a century later, in such a different world so far as the availability and technology of photography are concerned, I have said similar on many occasions. I am no purist – I am not sure what “purist” can mean any more. “Do you use Photoshop?” – well yes – and everyone does. Every single shot has been processed in one way or another; the question is whether you have had a part in the decisions as to how to process the image or have you left those decisions up to your camera?

My own aim in editing a photo is to create an image that looks as “natural”, as “real”, as possible, but which conveys to the viewer the emotional impact the scene had on me when I first saw it. That may involve quite extensive work in processing, but in general I don’t want that fact to be visible to the non-specialist viewer. I’m not sure I believe in “natural”, but I know what looks unnatural, and I avoid it.

Coming back to Frederick Evans – here is the image that first grabbed my attention in The History of Photography: A Sea of Steps, taken in Wells Cathedral. I find it an incredibly challenging and satisfying image. The shading, the way the eye moves through the picture, the movement and yet the peace of it, the sense of moving upward into the light – this is one of his best-known works, and for good reason. It seems to have been his favourite too. He wrote in the magazine Photography:

By use of a 19 in. Zeiss anastigmat on a 10 by 8 in. plate, I succeeded in getting a negative that has contented me more than I thought possible…. The beautiful curve of the steps on the right is for all the world like the surge of a great wave that will presently break and subside into smaller ones like those at the top of the picture. It is one of the most imaginative lines it has been my good fortune to try and depict; this superb mounting of the steps… 18 July 1903

The picture was popular with others too: Wells Cathedral put markers on the floor so that other photographers would know where to stand their tripods to get the desired perspective!

Frederick Evans died in July 1943, at a time when some of the very cathedrals he had photographed were in serious danger of destruction. He never made a fortune from photography, but he left a legacy of uplifting images which is unrivalled. I close this part of the blog with his amazing image of Lincoln Cathedral – rising with a sense of soaring power above thye smoky houses. It sums up his vision, I think – a spiritual and enlightening use of the camera.

I am in awe of his work.

Searching for light and peace

Evans’ architectural work seems to me to convey the sense of peace and wholeness for a number of reasons.

- A strong sense of the vertical – with the architectural verticals showing little convergence

- Perfect gradations of light and shade, often drawing the eye upwards

- Uncluttered, tranquil foregrounds

I came back to thinking about Frederick Evans this week for two reasons. I recently saw this image of the Doge’s Palace, Venice. Taken by my Oregon-based friend Jamie Bosworth, it gives me something of the same sense of perfection and wholeness as Evans’ work does. Evans would not have approved of the pigeon, of course, which is an intrinsic part of Jamie’s composition. But I LIKE the photo, in just the same kind of way as I LIKE Evans’ work. I am grateful for her permission to post it here.

To see more of Jamie’s inspirational work have a look at her site.

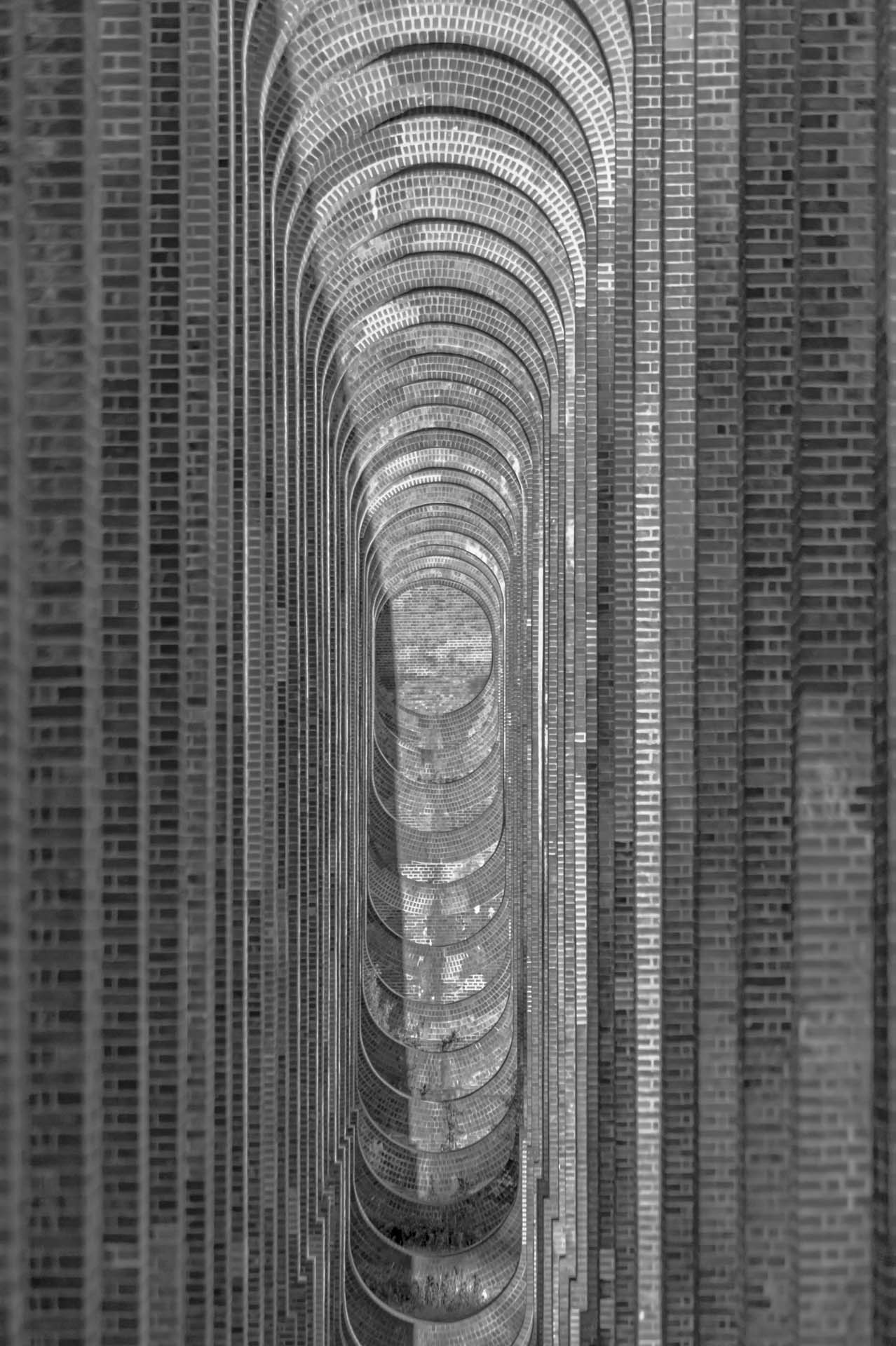

I was also really struck by the reaction of a work colleague to the image shown here. Cassie and I are great friends, but often laugh at how much we are chalk and cheese: if she is Beyoncé, I am Isaac Stern; if she is at home in the world of social influencers, I am the guy who thinks that capital punishment should be brought back principally for social influencers! But she liked this photo on Instagram, and we chatted about it. It struck me how what was, for me, an image that I had really worked on, both in the taking of it and the processing of it, could speak outside the confines of my particular, old cultural world.

The image was taken in the entrace archway of the Berlin block which used to house Berlin Mitte Salvation Army Corps. Anyone who knows Berlin (especially Prenzlauer Berg) knows this kind of building: a shops/office block at the front with an entrance way, then a courtyard, and flats in a block at the back. That arched entrance is incredibly dark when the street doors are shut, and the dynamic range along it, running from the deepest shade into the courtyard is pretty extreme. I had various attempts at doing justice to it.

In this case, I didn’t have an uncluttered foreground, and I was frustrated by the constraints of my 12mm rectlinear lens in getting the very top of the arch in. But the place always gave me a sense of peace and quiet, and I think you can feel that in this image.

Thoughts about those two images took me back to Frederick Evans, and I started wondering about the place of architectural subjects in my own photography. I am not referring to commissions I undertake for payment – I am talking about the pictures I take for the joy of it. Where is the search for peace and light in my own work? Here are a few examples that give me some satisfaction

That entrance-way in Berlin has been a bit of an obsession. I have returned to it and will do again if I get the chance. It is a favourite place, though I would be pushed to say exactly why. Light, shade and peace with the city bustling outside? Perhaps so!

To contact me to enquire about my photography – commissions or prints – use my Contact Form or just text (07983 787889) or email me at Andrew@AndrewKingPhotography.co.uk

Images from Frederick Evans (first half of article) are believed to be in the public domain and are posted here on the basis of fair use. Please notify me of any issues.

All other images copyright © Andrew King Photography except the Doge’s Palace which is © Jamie Bosworth.

Your architectural photos with the FZ1000 you shared are extraordinary! Thank you for this article on your blog.

Thank you so much for your encouragement!